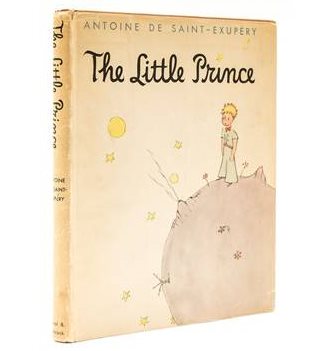

A fennec fox, the sand and stars, a baobab tree and a lad whose scarf unwinds to the length of a tagelmust, the face-covering turban worn by the nomads in the Sahara, are just some of the images that readers hold dear after finishing The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. The reach of the beloved children’s classic—about a pilot who crash-lands in the world’s largest sand desert and meets a small boy from a far-off asteroid—is as vast as the Sahara itself.

This year the story was translated for the 300th time since it was first published in French as Le Petit Prince in 1943. The North African languages it appears in include the darija (colloquial Arabic) dialects of Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria, as well as the Algerian Kabyle and Tuareg Tamasheq languages. In the last decade alone, there have been two different translations into Tamazight, the language of the Moroccan Amazighs, or Berbers, one in 2005 using the indigenous Tifinagh script and the other transliterated into Latin letters in 2007 with the title Amnukal Meiyn.

ULLSTEIN BILD VIA GETTY IMAGES

ULLSTEIN BILD VIA GETTY IMAGES

“I fell for the desert the minute I saw it, and I saw it almost as soon as I got my pilot’s wings,” wrote Antoine de Saint Exupéry, whose views of the Sahara from above began in the mid-1920s with North African legs of the mail route linking France and Senegal.

Saint-Exupéry, known to his friends as “Saint Ex,” did not come upon those desert images solely from his own imagination. Between 1926 and 1929, he flew single-engine, two-seater planes on various North African legs of the 2,900-kilometer mail route linking Dakar, Senegal, to Toulouse in southern France. Based for years in small coastal posts along the way, he flew over and lived among many earthly manifestations of the images for which The Little Prince is famous. So impressed by what he saw, some 15 years later he recalled them when he sat down to write and illustrate his book.

Readers bring their own interpretations to The Little Prince. This is especially true for Moroccans, who see much of their homeland in the book. Not just that sand and those stars, but that landscape viewed through the lens of a downed aviator awestruck at the sight of an uncommonly dressed stranger.

“Yes, the story itself may be universal, but one thing is sure: We Amazigh feel closest to its plot,” says the translator, noting that he and his people have heard such tales in their own homes, told by their own grandfathers. “The plot has many similarities to our Amazigh oral tales. And the word I used to translate ‘little prince’—amnukal—has an exact meaning that corresponds to a tribal chieftain.”

As The Little Prince’s aviator-narrator, a stand-in for Saint Ex himself, writes of his friend’s many questions upon their first meeting: “The first time he saw my plane, he asked, ‘Did you come in that thing? How? Did you fall from the sky?’ ‘Yes,’ I said modestly. ‘How funny,’ he answered. ‘You couldn’t have come from very far then.’” For the planet-hopping prince, just as for the Moors, a broken-down plane was as unimpressive a means of transport as the slowest camel.

"What makes the desert beautiful," said the little prince, "is that somewhere it hides a well."― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

Lahbib Fouad, who translated The Little Prince using Tifinagh script, agrees. The fact that the little visitor speaks “sometimes with a snake, a fox, a flower, a star [and] a volcano … coincides perfectly with the mythology and the cosmogony of the Amazigh,” he said when the book was published as Ageldun Amezzan.

Ghita El Khayat, a widely published Moroccan ethnopsychiatrist and anthropologist, has her own perspective on the marocanité, or “Morocco-ness,” of The Little Prince. As the founder of Editions Aïni Bennaï, one of Morocco’s leading publishers, she has brought out both its modern standard (classical) Arabic and its Moroccan darija translations.

“I consider it the most important book to be translated into dialectical Arabic, a book of special note because such a story is a gift from mother to child and should be read in what I call the ‘milk language,’” El Khayat says. Yet it is telling that her financial backers wanted it to be published first in classical Arabic.

“Even for those who say they believe in its value for children, many wanted it to be written in the language of formal discourse, as if delivered to and for adults,” she explains.

“In fact, I would have preferred it to be translated in my own mother tongue, the darija of Rabat,” she continues, “a language spoken only in the city of my birth, with as many Spanish as French loan words, rather than in a national darija that smooths away all of our particular vernaculars.”

A mail pilot’s forced desert landing could also be either smooth or rough, depending on—as the little prince often said—“On ne sait jamais,” (“one never knows”), until it is perhaps too late. Or in the words of Saint Ex, “The miracle of flight is that it merges man directly into the heart of mystery.” But to penetrate that mystery, one first had to survive the nosedive. As Saint Ex wrote in his memoirs:

"I fell for the desert the minute I saw it, and I saw it almost as soon as I got my pilot’s wings…. The nomads will defend until death their great warehouse of sand as if it were a treasure of gold dust. And we, my comrades and I, also loved the desert because it was there that we lived the best years of our lives."

The pilot’s first professional job was flying over the Sahara in a Breguet 14 biplane with an open cockpit and top speed of 130 kilometers per hour. Most of the time he was accompanied by a Tuareg assistant carrying a sword who would serve as bodyguard if they ever came down in the sparsely inhabited mountains.

The most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or touched, they are felt with the heart.― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

For two years in the late 1920s, Saint Ex made the desert his home, posted variously at Port Etienne (now Nouadibou) in Mauritania, and Villa Cisneros (today’s Dakhla) and Cape Juby (now Tarfaya) in southern Morocco where he served as station chief for 18 months.

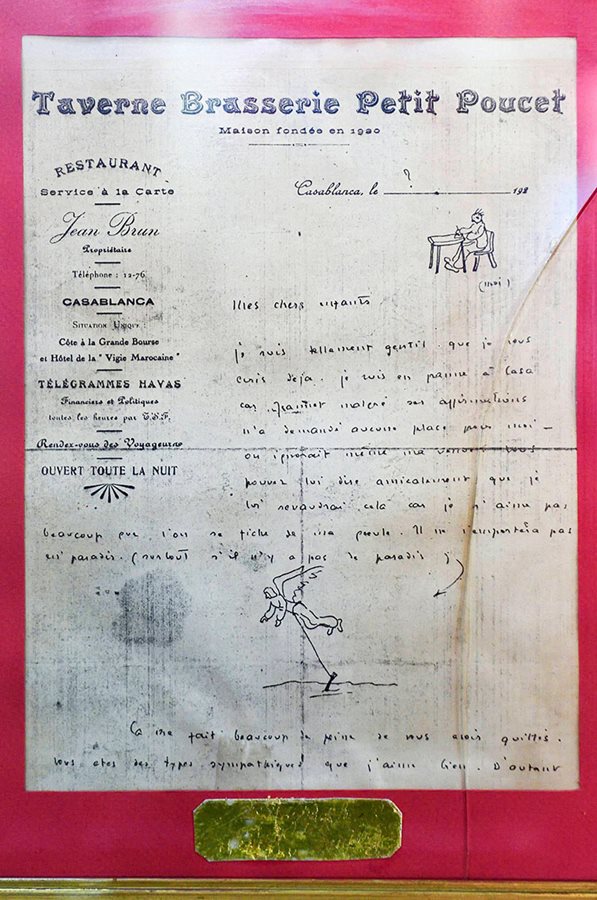

He returned to Morocco in the early 1930s, reconnoitering a direct air route to Timbuktu in Mali and flying the night legs of the Casablanca-Port Etienne line. The pencil sketches he made while waiting for dinner at the Petit Poucet restaurant after touching down in Casablanca still hang on its walls.

Saint Ex’s first crash experience came in 1926 on his very first flight across the desert while a passenger en route to his posting in Río de Oro, west of Villa Cisneros. No one was hurt, and a support plane landed safely at the site to take aboard the pilot. Saint Ex was assigned to stay behind to guard the wreck until relief could arrive. “Only two nights previously I was eating dinner in a restaurant in Toulouse,” Saint Ex wrote in his memoirs.

"But what I felt here nonetheless was immense pride. For the first time since birth my life belonged to me…. The sand sea was captivating. No doubt it was full of mystery and danger. Its silence came not from emptiness but rather intrigue, from the imminence of adventure. Night approached. Something slowly being revealed bewitched me—the love of the Sahara, like love itself."

In the book, Saint Ex’s narrator agrees when the little prince says that silence is beautiful. “It’s true,” he says, “I’ve always loved the desert. One can sit atop a dune, seeing nothing, hearing nothing, but something still stirs and glitters in the void.” Among the many oddballs the prince meets in his intergalactic travels is a geographer, bound to his atlas-piled desk waiting for a real adventurer to tell him where to find the oceans and deserts. “One requires an explorer to furnish proofs,” the geographer says. “It is very rarely that an ocean empties itself of water.”

You - you alone will have the stars as no one else has them.... In one of the stars I shall be living. In one of them I shall be laughing. And so it will be as if all the stars were laughing, when you look at the sky at night.― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

Two days before New Year’s Eve in 1935, Saint Ex was attempting to set a new Paris-to-Saigon airspeed record when he crashed again, this time in Egypt’s Wadi Natrun. This experience likely impressed on him the idea of the prince as a sort of lifesaver. After four days, nearing death and fighting thirst-induced hallucinations, he and his copilot were rescued by a lone Bedouin.

This was only the first of the day’s surreal moments. The rescue vehicle ran out of petrol not far from the Great Pyramid, where the Khufu solar ship would be found buried in sand 20 years later. When Saint Ex telephoned the French Embassy from the Mena House Hotel at Giza, the secretary warned the ambassador to discount the incoming call because it had been dialed from a bar after midnight. The Little Prince begins with a similar scene:

I had an accident with my plane in the Desert of Sahara six years ago. Something was broken in my engine … I had scarcely enough drinking water to last a week…. The first night, then, I went to sleep on the sand, a thousand miles from any human habitation. I was more isolated than a shipwrecked sailor on a raft in the middle of the ocean.

Saint Ex had been based near the Banc d’Arguin on the coast of Mauritania, and the nearby site of the famous shipwreck depicted in the Louvre’s painting “The Raft of the Medusa” by Théodore Géricault was certainly known to him. He would have dipped low over those very waters many times while flying the mail south to Dakar.

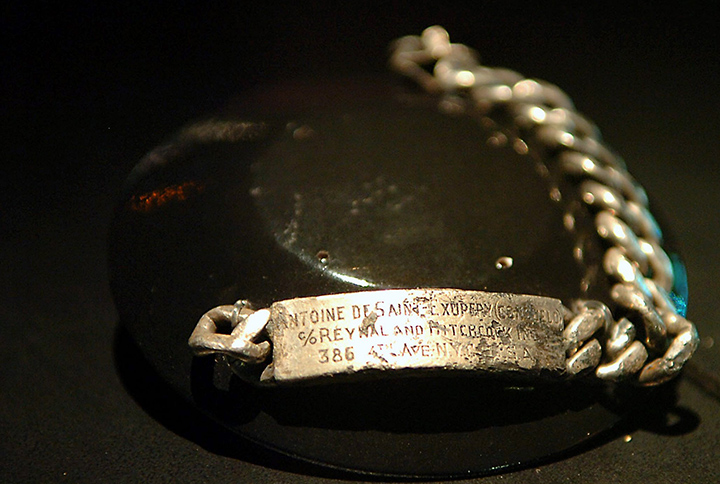

It was his third crash, while flying reconnaissance over the Mediterranean in July 1944, near the end of World War ii, that proved fatal. No cause was ever determined, but he perished in the same way he lived the best moments of his life—although he always said he preferred sand over sea. (Once after takeoff from a coastal airstrip, engine trouble forced him to fly dangerously low over the water. His passenger later reported that instead of looking at the control panel, Saint Ex had pulled out a sketchpad and was drawing the two of them as deep-sea divers.) At least, as he explained later, when you crash on sand you never run the risk of drowning. Any Tuareg of the desert, or even a little visitor from a waterless asteroid, would understand that perfectly well.

This article first appeared in AramcoWolrd October / November 2017